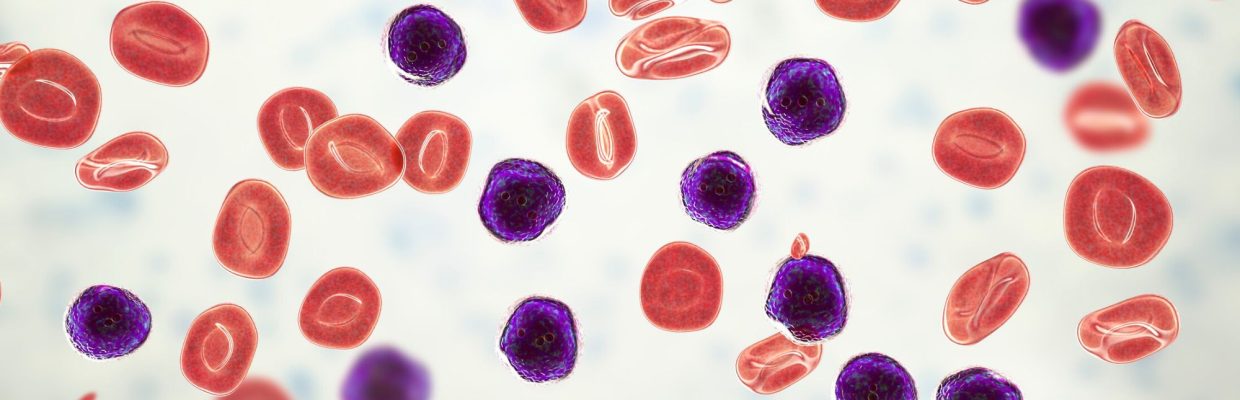

An international team of scientists has uncovered one of the mechanisms explaining how some leukaemias evade treatment by changing their appearance and identity.

Most children with the common blood cancer B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) have benefitted from huge improvements in treatment over the last 50 years and nine in every 10 children diagnosed will now be cured.

For those whose leukaemia does not respond to treatment, much hope has been placed on new antibody and immune cell-based treatments, such as CAR T-cells, which specifically target the surface of leukaemia cells.

Doctors, however, have seen that some of these leukaemias can evade immune therapies by stopping the production of the cell surface proteins which these therapies target, or even by switching to become a different type of cancer against which these new treatments are ineffective.

This is a particular problem for leukaemias caused by genetic rearrangements involving a gene called MLL.

Learning more about leukaemias

Teams from Newcastle University and Newcastle Hospitals, UK, the Princess Maxima Center in Utrecht and the University of Birmingham, have now revealed one of the mechanisms explaining how these’ ‘chameleon cancers’ change their appearance and identity.

Publishing in the journal, Blood, they have studied this cell identity switching behaviour in leukaemias caused by the MLL/AF4 fusion gene.

Dr Simon Bomken, Medical Research Council clinician scientist at Newcastle University and honorary consultant paediatric oncologist at Newcastle Hospital, and co-lead author of the paper, said: “ALL cells carrying this chromosomal rearrangement have long been known to be able to relapse as a different type of blood cancer, acute myeloid leukaemia (AML). When this switch occurs, the leukaemia becomes extremely difficult to treat.

“By studying MLL/AF4 leukaemias we showed that the switch can happen in blood cells throughout different stages of development in the bone marrow.

“Importantly, the switch can be a result of additional genetic changes that can be caused by chemotherapy itself. As a consequence, some leukaemias completely ‘re-programme’ themselves and switch identity from one cell type to another.”

The team found that this re-programming can be driven by changes to master control genes, including CHD4 which is normally required to switch off the genes important for development of AML.

Potential for future treatments

Dr Bomken added: “These results have important implications for our understanding of disease development and response to therapy.

“They begin to enable us to identify which patients are at greatest risk of relapse, thereby informing the choice of which treatments to use and when.

“In time specific therapies may become available to help prevent or overcome leukaemic switching and prevent the chameleon from changing its colours.”

The project was funded by Cancer Research UK, Blood Cancer UK and the Kay Kendall Leukaemia Fund.