Today (8 November) is World Radiography Day, marking 128 years since the discovery of x-ray by German physicist, Wilheim Röntgen.

Radiography is used by doctors to get a better picture of what is going on inside the body. Types of radiography include magnetic resonance imaging (MRIs), computerised tomography (CT) scans, mammography (breast scans) and ultrasound.

Here, we highlight the work of two radiographers, Rachel and Clare, who both work at Newcastle Hospitals in two distinct and interesting roles.

Rachel Brooks-Pearson

Rachel is a therapeutic radiographer and works at the Northern Centre for Cancer Care, based at the Freeman Hospital, as a Research and Development Clinical Specialist Radiographer. Newcastle Hospitals Charity funds two and a half days a week for Rachel to work on research.

In her role, Rachel studies ways to deliver radiotherapy – which uses high energy X-rays to treat cancer – more precisely to reduce side effects. She is currently carrying out research to look at how MRI scans can be used to plan radiotherapy for patients with prostate cancer.

Currently, radiotherapy treatment is planned using both a CT scan and an MRI scan. An MRI scan is done to gain a better image of the tumour area and organs at risk. The CT scan is used to calculate the dose of radiotherapy needed to treat the cancer.

Targeting tumours

Some cancer centres are using magnetic resonance (MR)-only scans to calculate the radiation dose, which is thought to be better because doctors only need to refer to one image, helping them to better target the tumour and preserve healthy surrounding tissue.

An MR-only approach could reduce the amount of time patients are in hospital and the severity of side-effects, both in the short and longer term.

The only centres in the world currently doing MR-only planning for patients with prostate cancer use fiducial markers to help radiographers line up the treatment beams.

Before these scans, prostate cancer patients receive an injection which contains fiducial markers – tiny metal objects about the size of a grain of rice. However, the injection can be an uncomfortable procedure for patients,

To understand how the MR-only method could work without the use of fiducial markers, Rachel, working with colleagues, led what is thought to be the first of its kind study to date.

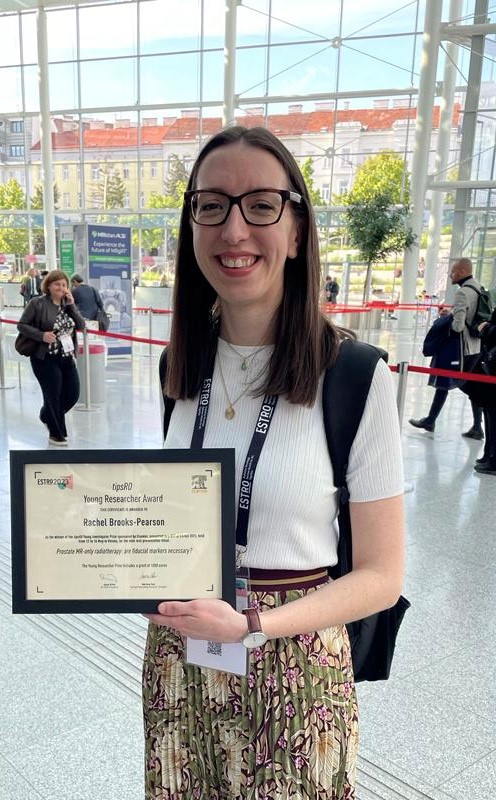

Prestigious award

The results showed that there was no significant difference between using fiducial markers or not in an MR-only approach. This work was presented at the annual European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology Conference and Rachel won the prestigious Young Researcher Award.

The findings from the research also supports extending MR-only pathways to other pelvic tumour sites and this will inform the next steps of Rachel’s research.

Clare and team

In clinical research, many studies rely on evidence provided through imaging, making the role of research radiographers an essential component in the research process.

The team is led by Superintendent Research Radiographer, Clare Moody, and includes three research radiographers – Louise Jordan, Leoana Matterson, and Philippa Bird. The team is supported by data manager, Mark Rickaby.

Every day is different in research radiography. The team can be scanning a knee replacement patient who is part of a clinical trial, or scanning cancer patients so that tumours can be measured to determine whether the cancer trial drug has been effective.

In a recent trial, research radiographers were involved in anonymising a dataset of historical plain film images for a large-scale artificial intelligence study. These images will be used to develop an algorithm for the automatic detection of a collapsed lung and correct medical tube placement.

Some patients who are on clinical trials regularly need scans, so the team has an opportunity get to know the patients and build a rapport with them.

A picture of the past

Did you know that radiography can be used in exciting history projects? The team worked with the historians at the Hancock Museum to visualise the mummified body within an Egyptian sarcophagus (a stone coffin). This enabled the sarcophagus to remain intact and still allow us to see how the body was preserved along with the precise location of the relics involved in the mummification ritual.

Find out more about our research here.